However, the reasons to start this space was not to be in the forefront of internet media (clearly to start a blog in 2009 is hardly innovative…), but rather to increase my text production (I vainly thought this would benefit my research writing) and to be able to report on my activities to my colleagues back at the museum in Sweden. So, I'll make a last ditch attempt to continue. For the first entry after the (long…) intermission, I will give you an update on my research of late.

Time is flying. We are well into October, only three months remaining in Zambia and I'm getting nervous of failing to getting the work done! Partly, this has to do with the scope of my research project (A reminder: young people involved in transport and trade in Western Province, their subjective understanding of their livelihood and futures and how government and organizations have attempted to control spatial movement from a historical perspective). There are so many different entries to the topic and so many contexts and locations in which to pursue my inquiries. So far, I've concentrated on the following:

1. Young people working as transporters: Mainly bus drivers and taxi drivers in Mongu as well as barge paddlers and 'call boys' (ñwañwazi), whom I have interviewed or in a few cases tried to befriend (with limited success, as I'm always also a potential customer - and customers need to be kept at a distance unless they start to question the need of the middle man). In addition, I've experienced (mostly suffered) the variability of thousands of kilometres of public transport together with fellow-passengers between Lusaka-Mongu-Kalabo-Mongu-Senanga-Sesheke-Lusaka, using boats, buses, taxis, bicycles and pickups.

Driving a taxi is a man's job (Photo by Rose-Marie Westling)

Driving a taxi is a man's job (Photo by Rose-Marie Westling)2. Young people working as traders: Mainly petty traders in Senanga and Kalabo. I have 'hung out' with a few key informants, sat in their little shops (and sometimes haggled with a curios customer), visited their homes, attended funerals. I have interviewed a larger number of traders in Senanga, women and men selling rice, maize, shoes, fish, 'boutique' (new clothes, made in China), salaula (second-hand clothing from Western Countries), hard ware and groceries.

3. History of spatial mobility in Western Province: Mainly at the National Archives of Zambia in Lusaka, where I have been going through the District Notebooks from the beginning of the last century, to find information about how colonial government(s) interpreted the mobility of local inhabitants, how they tried to monitor, influence and control spatial movement and migration. I have also done (fewer than I'd wanted) interviews with council workers and government officials on the current situation.

4. Interviews with former labour migrants in Kalabo District. This reflects point no. 3 above but also an interest I developed while carrying out research in Kalabo for my PhD (1999-2003). When doing surveys and interviews in the District, I found that up to three quarters of the male population above the age of 50 had long personal histories of periodic migration to (what is today) Zimbabwe and South Africa for work in the mines and fields. The narratives and recollections of these ageing gentlemen are important for what they tell us about the massive efforts to reorganize the physical (and mental) landscape of Central and Southern Africa, beginning at the start of the 20th Century and intensifying in the mid-1930s. The insatiable demand for cheap labour of the industrial centres of Southern Africa, led to huge investments in infrastructure, in institutions, roads and railways, that have shaped the way spatial mobility is imagined and how it is viable or possible even in the postcolonial state of Zambia.

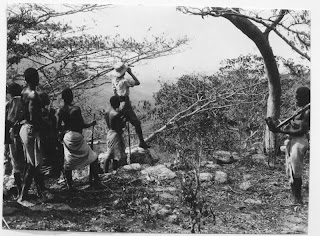

"Returning from Johannesburg, we walked majestically into the village!"

"Returning from Johannesburg, we walked majestically into the village!"The particular reason for writing about this right now, is a conference that will be held in Lusaka in August 2010. "A History of Consumption and Social Change in Central Africa 1840 – 2000" is organized as an element of the social historical research project "From Muskets to Nokias: Technology, Consumption and Social Change in Central Africa from Pre-Colonial Times to the Present" based at the University of Leiden, Netherlands and which encompasses several individual projects. Since these projects aim "to reinstating the African in the position of independent economic agent-independent economic agents engaged in the domestication of material products of the industrial world", my topic for the conference paper will be the material things that labour migrants brought home from the urban centres of Southern Africa and how these objects became entangled in the social changes that were taking place.

Apart from the research as such, I suppose it is natural that I've also become deeply entrenched in the lives of communities, friends and informants (especially with the handful families that I've known since 1998). This means I've bailed out friends in jail, helped mediate in disputes, given business advice (!), given education advice, attended several funerals, taken a battered wife to the Police, and (on numerous occasions) been asked to give my financial 'assistance', loans, gifts, or what you would like to call it. All this is at times very difficult, since I'm afforded (often contrary to my wishes) a position of authority and status that I dislike (or perhaps feel inadequate to fill). But let's face it: from the Kalabo perspective, I just turned 40, I am married with two children, I'm European, I drive a car, live in "a mansion" in Lusaka and (although I perceive myself to be a poor museum worker) I earn more in a month than most people in Kalabo do in two years. More importantly, my old friends in Kalabo are now important men and women in their families and communities and since I'm regarded as their age mate it is logical that I am deemed to be of similar stature. So perhaps I should just get used to it!

In August my family and I (and my mother and my sister and her family) tried to travel to Kalabo, crossing the Zambezi plain on a day when it just wasn't advisable. So we got stuck in a stream and had to turn back for a few days of irritating wait while the car was repaired. I suppose it sums up some of the conditions of travel in this marginalized region (by historical and current political neglect) For those interested, see the videos my sister and my brother-in-law made of the whole calamity.

My Toyota Hilux Surf having a bath

My Toyota Hilux Surf having a bathAnd on this note of seeming disaster, I end this entry with hopes that this blog will live yet another day.