Doing ethnographic fieldwork, in the contemporary meaning of the term, is all about the body. Movement or stillness. Either I'm walking around or I'm sitting down for long periods in travel, conversations, interviews, or note taking and writing. But this is an aspect of all human life and not in any way exclusive to anthroplogists.

Somewhat unique for anthros is that many of us self-consciously use our bodies as instruments to perceive and experience social life, in lieu of more formalized techniques like questionnaires (which some of us do use as well) or instruments found in a laboratory. In this sense the anthropologist's body is an instrument, albeit an extremely social (and imperfect) one. Observing and seeing 'others' is intensely social and (as any person belonging to a visible minority in any country might testify to) has a lot to do with power.

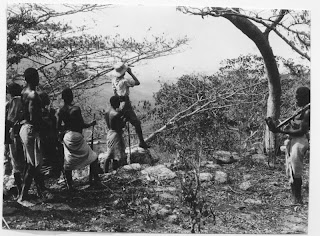

European so-called 'explorers' travelling through Africa in the 19th and early 20th century seemed to represent a form of seeing and registering that was not in the least self-conscious of these social and political dimensions. Their exploring was, according to their own understanding , an objective and impassionate project, a self-less endeavour for the benefit of civilization and progress.

Swedish Count Eric von Rosen (1879-1948) in what today is Zambia during his Cape to Cairo expedition (1911-12). Photo: Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm

Newer readings of some of 19th century travelogues, however, suggest that the rational and objective nature of such travels was largely a public image, created by authors after the fact to legitimize and canonize their achievements. This amounts to a particular literary style, forged by influential figures like Henry Morton Stanley and constantly reproduced by travel writers up to our own times. German anthropologist Johannes Fabian argues forcefully in Out of our Minds: Reason and Madness in the Exploration of Central Africa that the encounter between people like Leo Frobenius and his African hosts were not simply characterised by logic and impassionate observation, but also by ecstasis. Ecstasis, in Fabian's view, is a dimension of human interaction, of shared time and mutuality often made possible (in these situations of extreme and often violent power inequality) by sexual relationships, drug taking, music, dance and ritual. While often completely absent in published travel writing, records of such events and relationships may be found in diaries and travelogues.

The 'racial type' photographic genre. Photos by Eric von Rosen, Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm

In a third sense,the gendered, racialized and ethnified body comes into play. For instance, the transformation of my 'racial identity' (as perceived by others) involved in the travel from Sweden to the Zambian capital Lusaka, to the Provincial capital of Western Province, Mongu, and finally to the rural town of Kalabo, may be generalized and described in the following way:

This raises, on the one hand, many interesting social, cultural and historical features of the societies mentioned. On the other hand, it is also a personal psychological complexity that I have lived with for most of my life, at times painful and confusing, and thus not easily penetrated. I will return to this topic and discuss the "ethnic labels" in more detail in later blog entries.

There are other bodily transformations taking place in the journeys between Lusaka and rural Western Province that I would like to discuss here. My commuting life forces me to engage in intense body learning and un-learning.

Life in Lusaka for the well to do, like in many other modern social centres of the world, is geared towards controlling and shielding your body and avoiding engaging too closely with other people, or rather avoiding engaging closely with people of particular kinds and on terms that are uncomfortable to you. High walls, security guards, shopping malls, European high priced cafés, social clubs, sports clubs, international schools are all about such shielding. At the same time, contemporary life craves mobility and motor vehicles are what allows the affluent to be mobile while maintaining the required distance and privacy from the surrounding chaos of a third world country. In Zambia, people with means do not walk in order to get from point A to point B, they only walk (or the more adventurous of us) when excercising.

Photo: Rose-Marie Westling

In contrast, poor people walk everywhere, they fill the morning and early evening streets of the low density residential areas, on their way to or from their work places (as maids, gardeners, security guards). They cram themselves into minibuses and shared taxis, hustling and bustling and bumping into their fellow humans, sweating, arguing, laughing, eyeing one another. I don't want to romanticize this way of being in the world, it is often not enjoyed or entered into by choice, but at least it entails more talking, socializing, emotions.

My family and I fully participate in the affluent way of life when in Lusaka; we drive to school, to go shopping, visiting friends. We sit safely inside our electrified cement walls or inside the hull of metal, carefully locking the car doors (yes, the affluent warn each other about the dangers of driving through certain areas and of forgetting to lock the car doors) only disembarking at the shop or inside the gates of our homes (OK, unlike most other affluent people in Lusaka, we do not have a daytime guard or an automated gate, so we do need to get out to open the gate, contrary to much advice). Shopping centres without proper security (and thus the roaming ground for beggars, bums, street children and youth wanting cigarette money or your wallet) are gradually abandoned for secured ones.

The contrasts, deep inequalities and identity processes at play in this social system leads to resentments and feelings of inadequacy, which might explain some of the reactions I meet when I happen to break the expected patterns of mobility and the use of space. When walking in Lusaka, or using public transport, for example, people will stare and young men will sometimes laugh or jeer at the poor (or crazy) mzungu who is WALKING.

This does not differ much from life in Sweden, where some of the same mechanisms of exclusion, segregation and suspicion are in full sway, albeit with less stark and brutal expressions. My body can thus quite easily fit into the life of Lusaka, especially if I keep to the implicit script and do not try to confound the expectations of the people around me.

But turning to Western Province, things become a little more testing. Travelling from Lusaka to Mongu, to Kalabo entails transforming how I relate to people around me: from not interacting at all in Lusaka, to selectively acknowledging other people's presence in Mongu, to greeting and interacting with my whole body and all the time in Kalabo.

Learning new ways of being social (and constantly failing to act according to the established ways in the surrounding society) is sometimes an extremely tiring experience. After engaging (in body and mind) with the small town of Kalabo for eleven years, I'm still very far from knowing how to greet people properly and respectfully. Greeting is considered very important, since it confirms and expresses the particular relationships you have with a particular person. Not greeting respectfully therefore threatens such ties. But it is not an easy thing to get your body around, so to speak.

Photo: Rose-Marie Westling

To give you an idea, this is how a standard greeting may be performed in Kalabo between two Mbunda-speakers [translated Chimbunda-English]:

-Welcome!

[The visitor stops and crouches a bit, holding hands together in respect]

-Yes, Sir/Madame!

[the host will approach the visitor, and bow down to greet in the following manner:]

Clap

Brief handshake

Clap, clap

Brief handshake

Clap, clap, clap

-How are you this morning?

-We are fine, how are you doing?

-We are also fine.

-And your wife, how is she?

-She is fine.

-And your children?

-They are fine too? How about you, how's the family?

-They are just a bit [indicating a problem or illness of some sort]

If you are visiting someone, these greetings are followed by what is locally called muthimbo, which are short sentences, interspersed by acknowledgements, briefing on your recent travels and purpose of coming by:

-I came with my friend Michael here, he wanted to visit his friend Henry in Chimwaso [-eyo]. Michael is here to do research on the customs of our people [-aha]. So we borrowed these bicycles and set off around 10 hours this morning [-eyo]. We reached there around noon [-ehe]. Then we wanted to pass by the school and here to see how you were.

-Yes Sir/Madame. Thank you.

[Clap, clap, clap]

Photo: Rose-Marie Westling

Apart from the fine points of the Mbunda language (which I don't pretend to master in any way), greeting people in Kalabo requires knowing an array of body postures and signals that challenge those I've learned in my home society and also its ideas of sociality, gender and power. Crouching, curtseying, removing your hat when meeting an elder, holding hands with a male friend after the greeting has ended and we start walking down the street together, kneeling down and clapping in order to show exceptional respect (for example to chiefs or to a Mother-in-law) or accepting such courtesy from a woman who has served me a meal. Outside Kalabo, in the village universe, the (ideal) separation of male and female activities and bodies is so pronounced that daily life space is completely dissected into male and female spheres; men sit on stools or chairs, for example, while women sit on mats with legs outstretched before them.

As challenging and exhausting it may be to try to learn new ways of interacting with other people in the correct way, as gratifying it can also be when you feel that you are doing things in the right way. The positive confirmation and encouragement of your hosts, the relaxation felt in the company of same-age friends. But even then, such moments are fleeting and fraught with doubt or misgivings about things as they are.

Photo: Rose-Marie Westling